OKI- I'TAAMOMAHKATOYIIKSISTSIKOMI

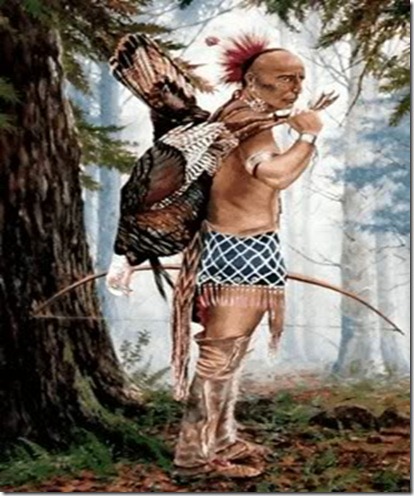

GREETINGS - - HAVE A MERRY CHRISTMAS AND HAPPY NEW YEAR FROM INDIAN COUNTRY

NOW YOUR INVITED TO A NATIVE AMERICAN CHRISTMAS DINNER

PAN-ROASTED MEDALLIONS Of TURKEY BREAST

1 10 to 12 pound turkey breast (have your butcher cut the eat from bone and skin and slice it into 2- to 3-ounce medallions. save and trimmings for the sauce.)

2 yellow onions, skin on, cut into eighths

1 carrot, peeled and cut into 1-inch; lengths

3 ribs of celery, washed and cut into . 1-; inch lengths

5 black peppercorns

2 bay leaves

2 sprigs of fresh thyme or 1/4 teaspoon dried thyme

2 cups dried cranberries

2 cups apple cider

1 cup dried currants

1 cup unbleached white flour

1/2 teaspoon sea salt

1/4 teaspoon black pepper

2 tablespoons canola oil

1/2 cup toasted pinion nuts (or substitute pine nuts)

Turkeys were among the few animals domesticated by early Native Americans. These birds provided meat and acted as sentinels, using their noisy gobbles to warn of approaching danger. In this recipe, cranberries, indigenous to the Northwestern tribes, are blended with the piñon nuts of the Southwest to create a tart, nutty sauce.

Preheat oven to 350oF. Place bones and trimmings from turkey in a heavy roasting pan and roast until they turn mahogany in color, about 1 hour. Transfer them to a heavy stock pot and cover with water. Add onions, carrot, celery, peppercorns, bay leaves and thyme; bring to a boil over medium-high heat. Skim the foam from the surface and turn down heat to a slow simmer. Cook for 3 hours. Strain stock through a fine-mesh strainer or cheese cloth, and chill overnight. In the morning, remove all the congealed fat from the surface of the stock. Reserve two cups of the stock for the Cornbread-Sage Dressing.

Return the defatted turkey stock to the stove and add the cranberries, apple cider and currants. Cook over medium heat until reduced in volume by half, about .4 cups. Season to taste with a pinch of salt.

While the sauce reduces, prepare the turkey medallions. In a pie plate, combine the flour with 1/2 teaspoon salt and 1/4 teaspoon black pepper. Dredge the turkey medallions in the seasoned flour and sauté in a small amount of oil over medium-high heat until golden on both sides.

Remove the cooked turkey from the pan and place the turkey on a paper towel-lined heated plate. Drain the oil from the pan, add the cranberry sauce and bring to a boil. Stir in the piñon nuts. Simmer until ready to serve.

To serve, place 1/2 cup of the Cornbread-Sage Dressing on a dinner plate. Top with 2 or 3 turkey medallions and ladle some of the sauce over the turkey. Contributor: Loretta Barret Oden. Yield: serves 8 to 12 Preparation Time:4 hours

CORNBREAD-SAGE DRESSING

for the cornbread:

1 cup organic, stone-ground cornmeal

1 cup unbleached white flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 teaspoon sea salt

1 egg

1 cup skim milk

1 cup fire-roasted corn kernels(can be found in Korean/Asian stores under teas)

2 tablespoons canola oil for the dressing

3 tablespoons canola oil

4 ribs of celery, diced

1 large yellow onion, diced

4 tablespoons poultry seasoning

4 tablespoons minced fresh sage

Before Europeans introduced wheat to the New World, most tribes used cornmeal as a major bread-making ingredient. This recipe calls for the addition of flour and leavening's to the cornmeal, which results in a lighter version of this Native American bread.

Preheat oven to 325oF. Combine the cornmeal, flour, baking powder and salt in a large mixing bowl. In a separate bowl, mix together egg, milk, corn and canola oil. Add the wet ingredients to the dry ingredients, and mix until most of the lumps are removed.

Pour batter into a 2-inch-deep baking pan and bake about 25 minutes or until the interior of the cornbread reaches 200oF. Remove cornbread from the oven and let cool. Scrape the cooled cornbread from the pan and crumble it into a large bowl.

Heat the canola oil in a medium-size saucepan over medium heat. Sauté the celery and onion with the poultry seasoning and sage until the vegetables become translucent.

Add vegetables to the crumbled cornbread and mix well. Add reserved turkey stock if the mixture is too dry. Transfer dressing to a baking dish and bake 20 to 30 minutes until heated through. Contributor: Loretta Barret Oden Yield: serves 8 Preparation Time: 20 minutes

PECAN STUFFED SWEET POTATOES

6 medium sweet potatoes

1 apple, peeled, cored, and chopped

1/3 cup apple juice or cider

1/4 cup currants

1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon nutmeg

1/4 nonfat milk

6 tablespoons chopped pecans

Gathered in large quantities by the Iroquois, pecans were added to breads, trail mixes, and all sorts of stuffing's. Preheat oven to 375°. Wash sweet potatoes, wrap in foil, and bake until tender, about one hour. Remove from oven and set aside until cool enough to handle.

In a medium skillet over medium high heat, cook apple in apple juice until softened, about 4 minutes. Stir in currants, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Cover and set aside.

Cut a thin slice off the top of each sweet potato and scoop out most of the

flesh into a large mixing bowl, leaving about 1/2-inch of flesh on the insides of the skins. Place potato shells in a baking pan and set aside.

Add apple mixture and milk to sweet potatoes and mix well to combine. Fill shells with potato stuffing and sprinkle the top of each with 1 tablespoon chopped pecans. Bake for 20 minutes or until hot. Yield: 6 servings.

THREE SISTERS SUCCOTASH

1 1/2 cups frozen or fresh corn kernels, thawed

1/2 cup chopped onion

1 cup chopped summer squash

1 cup chopped red bell pepper

1 tsp. ground cumin

1 tbsp. olive oil

2 garlic cloves, minced

1/2 cup defatted chicken broth

2 tbsps. chopped fresh cilantro

1/8 tsp. hot sauce

1/8 tsp. ground pepper

2 cups frozen baby lima beans, thawed

Place a large nonstick skillet over high heat until hot. Add corn, red pepper, onion, and cumin; sauté 5 minutes until vegetables are slightly blackened. Add summer squash, olive oil, and garlic; sauting and additional minute. Reduce heat to medium-high, add broth and remaining ingredients. Cook 3-5 minutes or until heated through, stirring frequently. Yield: 8-10 1/2-cup servings

BACON SAGE CORN BISCUITS

8 bacon slices

2 cups all purpose flour

1 cup yellow cornmeal

3 tablespoons sugar

5 teaspoons baking powder

1 1/4 teaspoons salt

1/2 cup plus 2 tablespoons chilled butter; cut into pieces

2 large eggs

6 tablespoons buttermilk

1 3/4 teaspoons dried rubbed sage

1 cup thawed drained frozen corn kernels

1 egg, beaten

freshly ground black pepper

Position rack in center of oven and preheat to 375°F. Butter heavy large baking sheet. Cook bacon in large nonstick skillet over medium-high heat until brown and crisp, about 8 minutes. Transfer bacon to paper towels. Crumble bacon into small pieces. Reserve 2 tablespoons bacon dripping; discard remainder. Mix flour, cornmeal, sugar, baking powder and salt in large bowl to blend. Add butter and rub in with fingertips until mixture resembles coarse meal. Whisk 2 eggs, buttermilk, sage and reserved 2 tablespoons bacon drippings in medium bowl to blend. Add to flour mixture and stir until moist dough forms. Mix in corn and bacon. Turn dough out onto floured surface and knead gently until smooth, about 8 turns. Roll out dough on work surface to 10x8-inch rectangle (about 3/4 inch thick). Cut rectangle into 12 squares. Place squares on prepared baking sheet, spacing evenly. Brush biscuits with egg glaze. Sprinkle lightly with ground pepper. Bake biscuits until golden and tester inserted into center comes out clean, about 25 minutes. Transfer to rack. Serve warm or at room temperature with lots of fresh butter!

AMERICAN INDIAN COLD CHRISTMAS CAKE

1/2 lb pecans, chopped

1/2 lb walnurs, chopped

1 lb shredded moist coconut

1 lb raisins

1 lb vanilla wafers

1 regular can sweetened condensed milk

Combine dry ingredients well. Pour in sweetened condensed milk and work through with hands so that dry ingredients are thoroughly saturated. Press into spring foam pan. Refrigerate for 2 days. My Cherokee ancestors used hazelnuts, dates and thick goats milk, then wrapped the cake in watertight leaves bound with vine and placed in cold running stream for several days. This is delicious and easy. Contributor:Ruby M. Harper. Yield: 4 servings

CHEROKEE JICAMA COLE SLAW

3 strips bacon

1 head shredded jicama, chopped

1/2 cup shredded carrots

1 celery rib; thinly sliced

1/2 cup whipping cream

1/3 cup sugar

2 1/2 tablespoon cider vinegar

1 salt and ground black pepper to taste

1 teaspoon paprika

Cook bacon until crispy in oven or on top of stove. While bacon is cooking, in large bowl, combine jicama, Carrots and celery. When bacon is done, let cool. Set aside.

In a small bowl, combine cream, sugar, vinegar and salt and pepper. Stir until sugar dissolves. Crumble bacon into jicama mixture. Mix well. Pour cream and sugar mixture over jicama/bacon mixture. Sprinkle with paprika. Toss well. Cover and refrigerate until ready to serve. Approximately 6 minutes.

http://nativechefs.com